For 14 or so years, I have been making a living building some of the largest audiences on the YouTube platform. I’ve seen a lot of videos and channels.

What I always find the most interesting, though, is that even after all of the time I’ve spent, all of the videos I’ve watched, all of the papers I’ve written here on Tubefilter, all of the conversations I’ve had with other strategists, all of the data analyses and spreadsheets and reports that I’ve presented–there are still new things to discover, analyze, dissect, and share.

At my agency Little Monster, we’ve been spending a lot of time recently thinking about macro programming strategies on YouTube. What we’ve boiled it down to is that YouTube channels employ one of four typical growth strategies:

Mass Upload

Search / Utility

Home Run Game

The Little Monster Method

You can see each of these strategies represented in the top 100 most viewed channels on YouTube each month, and all have pros and cons.

I’m going to lay out for you the foundation of each strategy, why it works, how and where it can fail, and the best practices required for each to succeed.

STRATEGY #1: Mass Upload

The T-Series Channel

The T-Series Channel

The Mass Upload strategy is exactly what it sounds like (and the antithesis of the Little Monster Method…but more on that later). Within this strategy, a channel is not trying to maximize every upload, they’re trying to maximize upload-ing. In short, the mass-uploader is placing as many bets (videos) on the board as possible. The basic proposition is more videos should equal more views. And it’s not necessarily wrong.

Of the top 10 most viewed channels in the last 30 days as of this publication, according to Gospel Stats, four of them, including the top two most viewed channels, T-Series and SET-India, have more than 15,000 videos uploaded. Twenty-three channels in the top 100 have uploaded more than 10,000 videos, and 43 channels have uploaded more than 1,000 videos (YouTube Shorts channels excluded).

This strategy is largely employed by media companies with large libraries of content, and it would be difficult to imagine an independent creator being able to pursue this strategy in a sustainable way. However, it’s not impossible.

Take gamers, for instance. A little back-of-the-napkin math would indicate that if a gamer was able to upload 10 clips a day, they would be able to get to 10,000 uploads over the course of nearly three years.

Large media organizations don’t have this problem. They can use the mass upload strategy to generate billions of monthly views, and when they do, there are a few high-level best practices essential to success.

First and foremost, for this strategy to work, a channel must recognize that what they are really building is a content library. This library will primarily thrive on:

1.1 Content Quality

The word “quality” is subjective here, but let’s be honest: content farms typically mass-produce garbage videos and rarely succeed in the long run.

5-Minute Crafts monthly YouTube Views from January 2019 to May 2021.

5-Minute Crafts monthly YouTube Views from January 2019 to May 2021.

On the other hand, the channel T-Series and similar brands succeed not just because of the volume of their library, but also the quality of the content therein. Just eyeballing on a cost-per-minute comparison, the videos being distributed on the T-Series channel probably cost 10x your average YouTube video or more.

The importance of this can not be understated. They are not just pumping out hot garbage on a plate. These are often music videos, movie trailers, or clips from TV shows and movies produced straight out of Bollywood that viewers are looking for.

That last bit is vital to the success of the Mass Upload strategy. If viewers are not looking for the type of content being mass produced, there’s a low likelihood of success with mass-uploading. Movieclips works because hundreds of millions of people are looking for these videos on a monthly basis.

Recent Videos From Fandango’s Movieclips

Recent videos from Fandango’s Movieclips

1.2. Never Slow Down

Once a channel has begun to move toward mass uploading, growth is predicated on keeping a mass-upload pace or accelerating. Constantly adding to the library means that the channel will constantly create new opportunities to be recommended to viewers by YouTube.

Most of these uploads will not generate views in the long run. Some content will get a second wind and spike for one reason or another. But every now and then a mass-uploaded video will crank out millions of views a day, every day, for years.

This is where the Mass Upload strategy pays off.

By having many thousands of videos in the channel library, the mass uploader does not need every video to generate thousands or millions of views on a daily basis in perpetuity. They only need a few to break through.

1.3. Thumbnails and Metadata

Mass Upload channels depend largely on their library to drive viewership (as opposed to the success of each new upload). Despite having nearly 200 million subscribers, a new video on T-Series rarely breaks 100,000 views. The vast majority of their 3 to 4 BILLION monthly views are coming from their library of past uploads (videos older than 30-90 days).

In order for these videos to do well over time and be consistently recommended in YouTube’s main arteries (suggested, browse/homepage, and search) they need thumbnails that accurately represent the video, and metadata that is clear so that people can find what they are looking for.

In a recent Creator Insider video, YouTube stated that the recommendation system “finds videos for viewers, not viewers for videos.”

So, in order for YouTube to find your video for a viewer, the content must be doing a good job of satisfying the viewers who have already clicked on it. Thus, the importance of accuracy. When YouTube sees viewers are finding what they are looking for in your video the recommendation system will continue to serve that video to similar viewers; or viewers looking for that thing.

Please note that you do not need a master’s in YouTube “SEO” to succeed here. There’s no amount or “secret sauce” of keywords that will help you rank here. Those days are LONG gone. What matters is:

Viewer satisfaction: Did you deliver on your promise? Did people hang out and keep watching?

Click through rate: You can’t satisfy viewers if they don’t click.

Accuracy: You likely won’t “rank” for a term or topic if the audience and/or the recommendation system believe your video thumbnail or title is misleading.

Mass Upload channels do not need a highly engaged audience to succeed, and may in fact be some of the least engaged with channels given how few views new uploads receive. This strategy is about being everything to everyone (Walmart), instead of being a specific thing to a specific audience (Tiffany’s). The play here is to simply flood the zone with endless uploads as fast as possible. Go fast, and accurately portray the videos in your thumbnails and metadata and you can succeed.

STRATEGY 2: “Search” & The Utility Channel

A “Utility Channel” is how we at Little Monster refer to a channel whose viewership is largely driven by direct informational value to the intended audience. These are essentially channels that make videos where the viewer is there to receive specific information.

This type of video is the second most sought after behind entertainment. In the September 2018 whitepaper YouTube Needs: Understanding User’s Motivations to Watch Videos on Mobile Devices, Google reported that of the 432 viewers they studied, 30.7% of the visits were reported as “to obtain information.”

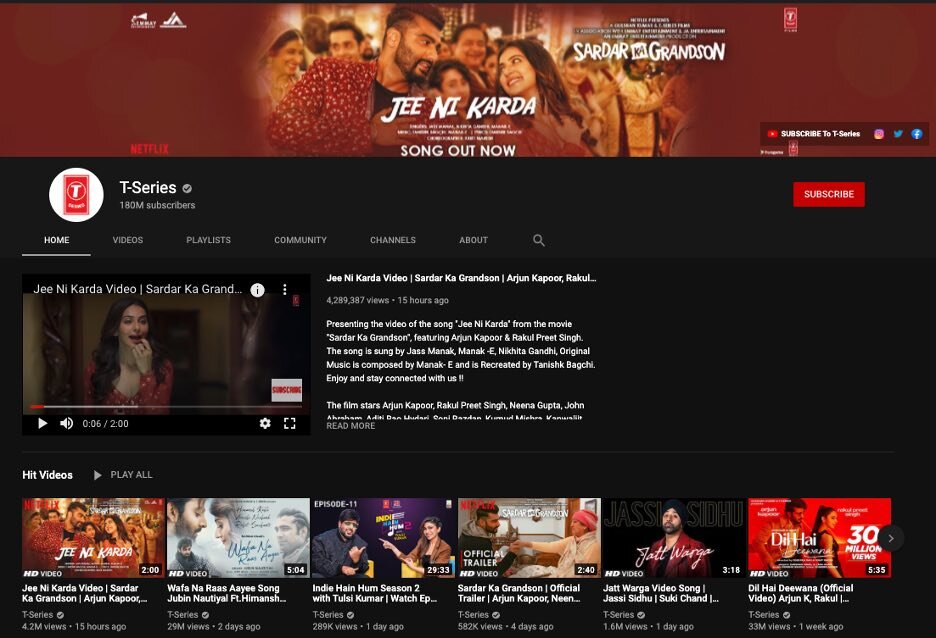

Huge audiences can be built here, but it’s difficult. Let’s take for example Khan Academy, whose viewership has little to do with how frequently they post, or the quality of any individual video. Khan Academy’s viewership has far more to do with when people are in school and looking for specific information on the classes they are taking. Note how their viewership thrives when class is in session, and plummets over the summer and over the holidays:

Khan Academy’s monthly YouTube views from January 2020 to May 20201.

While this is a pattern that generally seems to be true for similar educational or curriculum-based channels, other types of utility channels experience a strikingly similar need vs. viewership correlation.

Let’s take a car review channel, Redline Reviews. This channel regularly releases videos reviewing various cars, and their viewership can swing by as much as 300% upload to upload.

These two videos released within a few days of each other:

Two videos from Redline Reviews

What’s driving (pardon the pun) the viewership here is the need for information on a specific car. There are far more people interested in a brand-new model of car and in the price range of a Volkswagen ($32,000) than in the market for a car that has been around for a long time and in the price range of a BMW ($45,000).

Another type of channel that we at Little Monster call a utility channel are recipe channels. The viewership here is predicated on a potential viewer’s need to know how to make the food item being advertised in the thumbnail and title. Again, we still see sporadic viewership ranging from a few thousand views, to tens of thousands of views. As an example, here’s what the viewership on BuzzFeed’s Tasty looks like over 24 recent uploads:

Videos from Buzzfeed’s Tasty Channel

What these channels all have in common is that viewership is largely based on a potential viewer’s interest in the topic of the video. The viewer chooses to watch or not watch based on that particular video’s specific relevancy to them.

I’ve written and spoken extensively about the danger of having viewership be based on topicality previously. That said, in short, what this type of programming strategy leads to is unpredictable viewership, large swaths of your audience becoming less likely to be served your videos over time, and ultimately a mass upload strategy.

This leads to a mass upload strategy because that is the best way to succeed when you are a utility channel. This is true because the more videos you have that could potentially be relevant to a viewer, the more likely you are to gain viewership. The calculation is simple because if you want to grow as a utility channel, the more topics you cover (videos) the more potential viewership you will have. What is a library other than a utility to find the information you want?

Therefore, the same best practices that exist for Mass Upload hold true for a utility channel, with a few small tweaks:

2.1. Thumbnails

Your channel’s niche largely determines the thumbnail style that is most likely to get your videos viewed. Recipe channels typically use glamour shots of the finished food product, car review channels use glamour shots of the featured car, and so on. These selections accurately represent the video, but more importantly adhere to conventions audiences have become used to and conditioned successful channels to use. Essentially, those channels that have come before you in a given niche have done the hard work of finding out what viewers are most likely to click on through years of trial and error.

2.2. Being first

Utility can significantly benefit from being first to do something. When the latest tech or gadget comes out, those who are able to secure early access and get videos uploaded quickly tend to outperform others who come after.

The reason for this is that if your video is one of the first to be uploaded on a given topic, it’s a video that YouTube will already have processed the data around. This means your video, if it has decent metrics, will likely be served at the top of Search, in Homepage feeds, and at the top of Suggested, as interest and viewership spikes on a given topic. Additionally, there’s likely to be a small supply of videos on the specific topic of interest, and therefore your video is more likely to be put in front of viewers rather than others.

This becomes an upward spiral as the increase in views leads to higher clickthrough rates as the video generates more and more social proof in the form of views. This leads to YouTube continuing to serve your video to more and more people in more and more places (assuming other factors remain relatively constant).

2.3. Specific Niche

While mass upload channels can be far more broad (“movies,” “music,” etcetera), Utility channels must find as specific of a niche as possible. This allows for your audience to flow across your videos more seamlessly as your videos’ close relation to each other means they are likely to be more relevant to the viewer.

These are the main differences between the Mass Upload strategy and utility channel strategy in regards to best practices. However, there’s a poison pill in the utility channel strategy.

The pill is that viewership is based on the viewer’s interest in a topic, which makes it extremely difficult to build a sizable audience. This is true because it’s unlikely that the people you get to watch one of your videos will want to watch many (or any) of your other videos, because they’re only watching based on the value they can get out of the initial video they clicked on, or their interest in the topic of a specific video in the first place.

The audience is not there for you the creator, the style of the content, or the format of the show or video.

For example, look at these screen grabs from some of the top search results for “how to make chocolate chip cookies”:

Besides the different logos, these three channels are virtually indistinguishable from one another in terms of personality, style, and format.

These are the three key areas where a utility channel can distinguish itself. Focusing on developing these three areas can make a utility channel move beyond just providing informational value, and allow them to provide “entertainment” value or “connection” value as well.

“To connect with others” was the third main reason people came to YouTube in Google’s study. This connection specifically relates to how a personality, talent, or host connects directly to their audience.

If there were a clear, repeatable science to creating this connection, there would be millions more full-time YouTubers, movie stars, and famous musicians. However, I don’t think this is some mysterious X-factor that you either have or you don’t. It can be honed and it can be leveled up through practice and training.

A common trope in our industry is “be authentic.” Hell, I’ve said it myself when advising creators at Little Monster. But I’ve never heard someone actually describe what that means in practical terms or at least define it in a way that is universally applicable.

My advice would be to study the creators on YouTube that you or your audience connect with. What do they do that makes you want to spend time with them? Find what that is, and what that is about you or your talent, and double down on that. Take improv classes. Practice making videos. I’m not saying you’ll be the next PewDiePie, Zendaya, or Cardi B, but improving your skills here can increase your chances of finding success on YouTube.

As it pertains to style, that’s simple and straightforward. Do people watch your videos because they really love the unique style of video you’re creating? Is there something you can do to make your style just a smidge or two better than those in your vertical? If so, this can make you and your content stand out amongst the sea of competitors.

The lovely thing about style is that it’s far less subjective than connection, there are far more resources to make yourself better at the actual art of video creation, and it doesn’t take a lot to really stand out.

When speaking to Utility channels, the aspect of content creation that Little Monster focuses on most is format. I’ve written extensively about how a channel can distinguish itself by way of format in my Taxonomy article here on Tubefilter. I encourage you to read that article with an open mind, and to keep in mind that what I am proposing in that article is a methodology about how to create a new format, not just ape what is already being done successfully.

What we are essentially advocating for here is moving a channel from having a Utility Channel approach (Mass Upload) to a Little Monster Method strategy. The reason for this is that by and large, most media companies and independent creators (who, by the way, are media companies whether they recognize it or not) will not be able to compete against the Mass Upload strategy. If you can out-upload the Mass Uploaders, by all means, give it a shot. But you’re more likely to bankrupt yourself or burn out than overtake a channel that already has thousands of videos and is adding more daily.

The vast majority of this type of channel will have to win not through quantity but through quality. Finding your footing in personality/talent, style, or format is the surest way we at Little Monster have found to do that.

STRATEGY #3: The Home Run Game

Channels that play The Home Run Game upload many different types of videos until one really takes off (home run!). Once you’ve hit a home run, you double down on whatever worked, the “value proposition” of that particular video, be it format, style, personality, topic, or some combination of the four.

We see this often in channels that have been around for a long time before suddenly exploding with growth. A few top examples of this are channels like Cocomelon, PewDiePie, and MrBeast. MrBeast uploaded well over 100 videos and was active on YouTube for six years before he reached 1,000 subscribers.

3.1. Playing The Home Run Game

This strategy can work in a few different scenarios:

You have an understanding of your channel’s core value proposition but can’t really get traction in your niche or vertical. In this scenariom it makes lots of sense to explore different styles, formats, and talent or performance styles.

For example, let’s say you’ve built a decent-sized audience in the home improvement vertical. You know your audience generally wants and expects you to talk about interior design. Your typical video shows you doing some sort of DIY project in your home.

Instead of doing the same thing in each successive upload, take some swings at the fences. Try reacting to various clichéd themes, critiquing celebrity homes, remaking things in a celebrity’s home, go handheld instead of on a tripod, and so on.

You have a large competitive advantage, like a brand. If you’re a media brand, you likely have a library of content. Is there something you can do with this library that others are not? A different format or style of video? If you’re a non-media brand can you leverage your access to events, celebrities, or products to get an advantage over people in this space? If so, take these swings.

Note that if you do hit a home run here, you’re going to want to move everything else you are creating to another channel or spin this type of content out into a separate channel. YouTube channels are designed for one core value proposition. Two competing shows or types of value propositions on the same channel will hurt both.

You have a new channel and therefore have room to experiment with no consequences. For people starting out on YouTube this is the perfect time to try things that are outside the norm. Every minute, 20+ DAYS worth of content is uploaded to YouTube. Do something unique to stand out in this content tsunami.

In the long run, the Home Run Game strategy should be considered a means to an end, with the end being a solidified, clear value proposition. If a channel always swings for the fences with wildly different programming, the audience will have no idea what to expect when YouTube serves them one of its videos.This will alienate both the audience and the recommendation systems. As a mentor once told me, you want to be dependable, but not predictable.

The home run game is not moneyball. The home run game is trying to become the Yankees on a Norwich Sea Unicorns budget.

STRATEGY #4: The Little Monster Method

Moneyball, the 2003 book and 2011 film starring Brad Pitt and Jonah Hill, chronicles how Billy Beane took the Oakland A’s to the playoffs in 2002 and 2003, with one of the lowest team salaries in the majors.

Essentially, Beane built a team by leveraging data to select and utilize players who were statistically highly likely to lead to wins through their combined impact, without relying on individual superstars.

The Little Monster Method is moneyball for YouTube channels.

We use data to create and distribute videos for our clients that are highly likely to succeed with our client’s audience and thereby the YouTube recommendation system. Like Beane, our clients’ videos win because they are analytically designed to do so.

Our method is based on the premise that a YouTube channel should serve one audience a single core value proposition. We use the data in YouTube analytics to understand exactly what that audience is most interested in, and then super-serve them what they want.

This is a 360-degree approach to content creation, analyzing and optimizing the:

Value proposition of the channel

Format of the content

Style of the content

Talent on screen

Topics of videos

Length of the content

Thumbnail design

Title structure

The two most important elements in this strategy are the Value Proposition and the format of both the channel and videos.

4.1. Value Proposition

A value proposition is essentially the answer to the question “Why does someone watch your videos/channel?” It can be a concept (“they will be inspired”), format (it will be a reaction video), style (a Wes Anderson film), personality (a specific person will be in the video), or a topic (videos will always be about surfing).

The value proposition doesn’t need to be universally true for every viewer, but it does need to be universally true for every video. For example, if we asked MrBeast’s fans “Why do you watch MrBeast?” you would get a lot of different answers. However, from MrBeast’s point of view, every video is a larger-than-life spectacle (therefore, that’s the value proposition).

4.2. Format

For MrBeast, the other elements (format, style), while important, are not beholden to this same singularity. For example, he can do a Challenge video format in one video, and in the next a reaction/listicle video format.

In the video below, MrBeast is utilizing a very classic Challenge video format, where three teams are competing to win a prize. Here, it’s a house:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f0c7pSCoZqE

Utilizing a completely different format (reaction/listicle) MrBeast made a video where he tips waiters and waitresses with real gold bars:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Rmf6T_Ewt38

As you can see these videos are completely different formats, but still deliver on the larger-than-life spectacle value proposition.

For MrBeast, format is less of a core necessity than for others. This is actually true for the vast majority of “influencers.” Quite often, once someone achieves influencer status, the core value proposition has become the creator.

MKBHD is a great example of a channel that has made personality it’s core value proposition. MKBHD’s core value proposition is that you get to hang out with him. He’s cool, transparent, humble, engaged, excited, and unflinchingly himself. He also has some of the slickest and most stylish “tech review” videos on the platform. Unlike other tech review channels, his content doesn’t adhere to a singular format at this point, because it doesn’t need to.

However, format as a core value proposition is key for channels like Complex’s First We Feast, MTV’s Wild ‘N Out, and Binging with Babish.

First We Feast by and large has two primary formats (in this case, named shows)–Hot Ones, and The Burger Show. By and large Hot Ones outperforms The Burger Show.

Recent videos from Complex’s First We Feast Channel

On MTV’s Wild ‘N Out, the rap battles and highlights from the show dominate the other types of content they’ve tried:

Video thumbnails from MTV’s Wild ‘n Out

And for Binging with Babish, his main show beats out the secondary show Stump Sohla regularly.

Recent videos from Babish Culinary Universe

The reasons these secondary shows all underperform (and there are countless examples) is because they do not match the core Value Proposition of the channel fully, as these are channels that are more reliant on a viewer’s interest in the format.

You may be asking, why does this matter? What’s the harm in putting multiple value propositions or multiple formats into one channel?

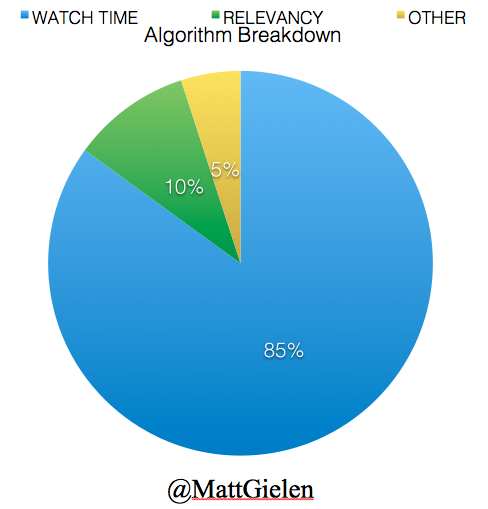

The problem lies in how YouTube’s recommendation systems are built and how audiences behave. To make recommendations, the YouTube recommendation system uses:

A viewer’s past viewing history (clicks, duration of view)

A viewer’s past engagement history (likes/comments/surveys)

Contextual information (device, location, time of day, etc.)

Collaborative filtering (How other similar viewers have engaged with a video)

Video stats (clickthrough rate, average view duration, user feedback)

This system is designed to treat each individual user independently, creating a YouTube that is customized specifically for them.

If a viewer has historically clicked on your videos regularly, watched them, and given positive feedback (implicitly, like spending a long time watching and then watching a bunch more of your videos, or explicitly, like filling out a survey about your video positively), YouTube will continue to serve them your videos. More importantly, YouTube will use this data and suggest your videos to similar viewers.

Now, let’s say you switch up your formats or introduce a new show concept and YouTube feeds the new format or concept to your audience…and they don’t like it. They don’t watch for very long, click “like,” or leave comments…You’ve changed the value proposition, and YouTube is going to ding you for it.

This is because YouTube is incapable of deciphering between two different series on a YouTube channel. The recommendation system is built to simply understand if a viewer clicked, watched, and enjoyed your videos the last few times they were recommended to that viewer.

Like we see with The Burger Show, Quarantine Workout, and Stump Sohla, audiences haven’t responded with the same enthusiasm, so YouTube serves these new concepts/formats to fewer people in their audience.

But it gets worse. Because YouTube is incapable of deciphering between different shows on your channel, it becomes less likely to serve your audience ANY of your videos in the future, including the type of video the audience initially liked. The introduction of a new value proposition is a big gamble–and from Little Monster’s point of view, a bad bet.

There are billions of videos on YouTube and 500 hours’ worth of content is uploaded every 60 seconds. Why should YouTube waste its time and impressions trying to decipher which specific videos from a channel a particular viewer might be interested in when they could just show them any of the millions of other videos with better metics from channels the viewer has a greater probability of enjoying?

In other words, YouTube is not going to subsidize your bad bet. Their value proposition to the audience is that there is nothing in the world as entertaining as YouTube. If your new series doesn’t support that idea as well as your previous series did, YouTube has to shield people from it in order to live up to their value proposition.

In addition, the impressions that could have been going to your high-performing videos have been going to these new concept/format, underperforming videos–a double whammy for you and your content.

All of this causes your viewership to bleed over time, and eventually leads to “channel decay,” possibly to the point of no return.

This is why channels that make the mistake of having multiple value propositions decline in viewership.

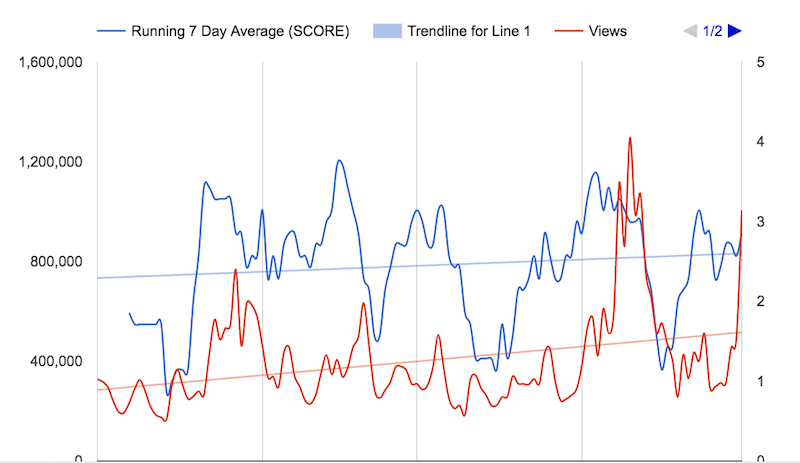

Don’t just take my word for it–here’s a graph of Babish Culinary Universe’s viewership over the last 12 months. The second show, Stump Sohla, first appeared on the channel in September of 2020:

Babish Culinary Universe monthly YouTube views from May 2020 to May 2021

Beyond value proposition and format, the other elements of a programming strategy all adhere to the same principles in the Little Monster Method.

4.3. Talent/Personality: Are we seeing high CTRs but low relative average view duration? If this is married to other data (like negative comments about the main person onscreen) this might be an indication of a needed shift in performance or talent. If there are multiple different talent onscreen, is there one that gets more positive comments? Are there there spikes (good) or click off (bad) when a specific talent or character is onscreen?

4.4. Style: What style of video does your audience most like to watch–handheld multi-camera with quick cuts, or a locked-down single camera and slower pacing? Here we’re looking at the difference in average view duration and average percentage viewed, and similar deep metrics.

4.5. Topics: Are there certain topics within your niche that an audience is most interested in? Are there topics they are clearly not interested in? We do this by labeling every video, averaging the viewership across those different topics, and then we double down on the topics that generate the most interest. Ideally a channel is not using topics as a primary value proposition. When topics are your primary value proposition, your viewership is tied to things outside your control. For example, look at all of the Five Nights at Freddy’s channels that don’t even upload anymore because interest in the IP has plummeted.

4.6. Tactical Analytics: When we look at more tactical items in The Little Monster Method–titles, thumbnails, video length–our goal is to make the video the most “clickable,” without being misleading. Here we’re going to be analyzing things like the velocity of the video. Essentially, is the video getting more viewership in its first one hour, two hours, or ten hours than our other videos? What is it about the programming choice, thumbnail, and title that is causing this higher relative clickthrough rate? How many faces should we put in a thumbnail (if any)? Should we use text? Are we going for a clear value proposition as to what the video is about, creating an information gap, or teasing the viewer with our thumbnail and title combination? Do videos that fall between 17 minutes and 23 minutes on average generate the best average view duration for more viewership in the long run or is there a different sweet spot in length?

4.7. Timeline & Evolution: We break down content and best practices for a channel over the long run by looking at what worked at the 30-, 60-, 90-, and 365-day mark. Combining analytics over the short- and long-term and teasing out the often subtle differences helps Little Monster create maximum impact and reach quickly and over the lifespan of a video.

At Little Monster, we’re not looking for “viral” videos or home runs. We’re looking for videos that are more likely to get on base than they are to strike out. We’re using all of the data both on-platform and off-platform to make extremely well-informed decisions as to what combination of factors in strategy and tactics will lead to audience growth. We’re playing moneyball, and we’re winning. You should too.